Nomina debent naturis rerum congruere

Taste in languages resembles taste in other matters; which is to say, tastes are singular, individual, and often hard to explain. To examine them may be to cut the ball open for its bounce. Tolkien's are no exception. For example, in letter 213 Tolkien rather curiously asserts that he "dislike[d] French and prefer[red] Spanish to Italian," which is an almost total reversal of common opinion on the matter. Is French not famous as the language of love and beauty? Later he also states that he "love[d]... especially the Welsh language," but that "of the Irish language [he found] wholly unattractive," and in various places like letters 257 and 163, he states his favorite influences as Finnish, Welsh, and Gothic. And it is hard to deny these influences, looking at the extreme similarities between Quenya and Finnish and Sindarin and Welsh. But we shall attempt to examine a few matters in phonaesthetics, a word (likely) invented by Tolkien himself to mean "the aesthetic quality of sounds in language".

In the matter of linguistic beauty, Tolkien stood away from general consensus. The principle of "linguistic arbitariness" was cutting-edge in his day: it came onto the scene with Saussure in the late 19th c. and reached a peak in popularity with Chomsky in the mid 20th c. This principle states that the association between sound and meaning is necessarily arbitrary; according to this hypothesis, a TREE is a "tree" /tri:/ not because the phonemes /t/-/r/-/i:/ have some "tree-like" quality to them, but simply because the meaning TREE has been arbitrarily mapped onto those phonemes.

As time has gone on, more cracks and caveats have appeared in this theory. The kiki-bouba effect is now quite widely known; the reader may explore that topic on their own if unfamiliar. A more intriguing, broader example would be another study found in the book Sound Symbolism pp. 76-93, in the study "Evidence for pervasive synesthetic sound symbolism in ethnozoological nomenclature" by Brent Berlin. The study examines bird and fish names in Huambisa, a native language of the Andes to which none of the participants had ever been exposed. In the following (abridged) list of pairs of fish and bird names, which ones are birds?

(1) chunchutkit, mauts; (2) chichikia, katan; (3) teres, takaikit; (4) yawarach, tuikcha; (5) waikia, kanuskin

(Answer: respectively first, first, second, second, and first)

Of the chosen example pairs above, 90+% of respondents correctly identified the bird name (though general participant accuracy was lower; around 58%, which was still very statistically significant given the number of responses). The study also concluded that bird names had more [i] (like in machine) and fish names had more [a] and [u], and theorized, based on other papers, the cause to be that [i] has a higher F0 (base frequency) than [a] and [u]. This tendency apparently extends both to onomatopoeia in other languages and even into the animal kingdom.

So sounds do have meaning; but we have wandered. What, precisely, characterizes the sound-systems of Tolkien's invented languages? And is there sound-symbolism in such? For this we need two more discussions, respectively addressing vowels and consonants: that of "balance" in phonetic inventories and that of "sonority".

First, compare the inventories of contrasting sounds in both the following unnamed languages among those mentioned by Tolkien in his letters. The precise value of the symbols is irrelevant, since what matters is the distribution; but know that the parallelogram is a literal representation of the mouth:

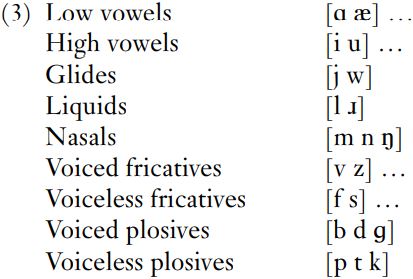

Sonority is generally the loudness of individual sounds; another way of thinking about it is that 'louder' sounds involve more continuous air release, i.e. less restriction of the vocal chords and mouth as they produce sounds. In fact, sounds are thought to form a hierarchy in this manner as follows:

An interesting property of sonority is that, near-universally among all languages, syllables tend to have higher sonority in the middle and lower sonority around the edges. This property explains why common syllable nuclei tend to be more sonorous sounds like vowels ("bob") or also more sonorous consonants like the <l> in the second syllable of <bottle> "bah-dl" or, in American English, like the <r> in <bird> "brd". It also explains why syllables like "grat" are acceptable in English, but syllables like "sktf" are not. Theoretically, what is most desirable are syllables that look like mountains, rising in sonority then dipping back down, as in this diagram of the word "splinter" (note that s+C is one of the few initial clusters in English that violates the sonority hierarchy):

The principle of balancing distinctiveness and ease still apply: while more sonorous sounds are easier to make, they are also less distinctive from one another because they have less occlusion and thus less unique air flow. As well, sonorous sounds are harder to make in sequence. So the sonority hierarchy allows languages to be distinct and easy at the same time. "Open syllables" are those that end in vowels; ending in consonants is less sonorous.

But Tolkien's languages have an odd property: they are extremely sonorous; which is to say, they use as many high-sonority sounds as possible. The opening lines to the Lord's prayer in Sindarin read: "Ae Adar nín i vi Menel / no aer i eneth lín / tolo i arnad lín / caro den i innas lin". Every vowel is between two consonants; and every consonant is high on the sonority hierarchy! And in fact, there are two! total voiceless plosives (in: tolo, caro), since that is the lowest rung on the hierarchy. The clusters are all at most two consonants, one of which is always a high-sonority sound like a nasal or liquid. About half of the syllables are open, which is extraordinarily high when compared to native English words (a fun exercise would be to count open and closed syllables in "Uncleftish Beholdings", a scientific article written wholly with native words). It is a similar, though less extreme, story with Quenya, e.g. "A Elbereth Gilthoniel / silivren penna míriel": note again the near-complete avoidance of voiceless plosives and the clusters all involving liquids or nasals. Were one to draw a chart of a given text in Elvish, there would not be mountains but rolling hills.

Compare the only known text in the Black Speech of Mordor, which Tolkien designed to be ugly and harsh: "Ash nazg durbatulûk / ash nazg gimbatul / ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul." Almost every syllable is closed and/or has a stop and all words end in a consonant; note the complex and awkward consonant clusters. Oddly, Tolkien seems to dislike (the more sonorous) voiced fricatives like "gh" and "z", the former also because it is made far back in the mouth; so also with a dislike for "sh", which produces measurably much more turbulent air than "s" (as seen in e.g. a spectrogram). Perhaps this also explains his distaste for French, which has much of "z" and "v" and "zh" and whose "r" sound is more or less a guttural "gh". Tolkien preferred the less 'buzzy' unvoiced fricatives and the less turbulent, airy voiced stops. With a hand in front of the lips one can feel the rush of air in "ta" and the lack of air in "da," and with a hand on the throat one can feel the buzz of "zzz" and the silence of "sss." But there is a more precise measure of sonority.

The average sonority of different languages has been both studied and quantified. There appears to be a strong link between climate and sonority of language: the colder the clime, the less sonorous the tongue. Though it's very hard to find data directly comparing the languages Tolkien measured in his letters, one study (Maddieson 2018) did include Finnish and found that it was extraordinarily sonorous, scoring well above the included Indo-European languages completely bucking the cold climate trend. Another indicator of this is phonotactics (the permitted structure of syllables): while English allows up to CCCVCCCC (e.g. "strengths", phonetically s-t-r-E-ng-k-th-s) or 7 consonants for one vowel, Finnish only allows up to (C)V(C); and the more consonants, the less sonorous. Quenya and Sindarin both appear to be CVC, like Finnish or Italian but unlike English or French; Welsh appears to be (C)(C)V(C). But these measures are all rather non-numerical: a more serious scholar than I would use the methods in (Fought et al 2004) to compare with various languages Tolkien liked and disliked.

All this is not to say that Tolkien looked at vowel charts and read about the phonotactics of languages to decide his opinion on them. He listened to them, or read them, and made his decisions based on how the languages flowed. Did they run coarse, dragging and smashing into jagged consonants? Or did they flow from gentle, sonorous sound to clear vowel and back again, rolling in a rhythm as a boat rocking over small waves? A person may prefer thrill rides and harsh contrasts, or silken sailing and gentle rowing; Tolkien was a fan of fair weather and rolling hills.

-LN

1 comment:

I have so many questions now! But also thoughts: I am very curious how this understanding of sonority will apply in our discussion of Style—what kind of sound effects Tolkien gave to the speech of different characters as well as to the poetry he composed for the different peoples. It makes a great deal of sense to see the Elvish languages matching Finnish and Italian on vowels, giving a specificity to Tolkien's "flavor" metaphor for different languages: they resound differently in the mouth! RLFB

Post a Comment