In class, we discussed the possibility of lembas as the bread of the Eucharist. However, considering Tolkien’s participation in World War I, I believe it should be considered the Elvish version of hardtack. The cram of the human Dale-men is clearly the human parallel to hardtack but, similar to how different nations had their own hardtacks, I believe lembas should be considered as a magical hardtack. According to Christopher Tolkien, “Lembas is the Sindarin name, and comes the older form lenn-mbass ‘journey bread’” (Christopher Tolkien, The Peoples of Middle Earth, 408), mirroring the function of hardtack.

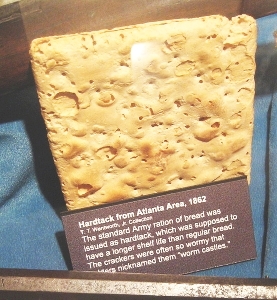

Hardtack served as the typical military or ship’s ration before the invention of MREs. It was an incredibly dense and unbelievably hard biscuit or cracker made of water, flour, and, occasionally, salt, that was valued for its longevity and inexpensive cost of production. Hardtack was a ration of last resort and was only eaten when nothing else was available, and the Elves’ description of lembas mirrors this purpose:

“[lembas] are given to serve you when all else fails. The cakes will keep sweet for many days…as we have brought them. One will keep a traveller on his feet for a day of long labour.” (J.R.R Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 371)

Even the description of lembas as “very thin cakes, made of a meal that was baked a light brown on the outside” mirrors the appearance of hardtack.

Hardtack was a notoriously loathed food, with many generations of soldiers and sailors all loathing its existence. A soldier in the American Civil War voiced the complaints of many when he wrote about what it was like to depend on hardtack for sustenance:

“A year ago to-day I cradled rye for Theron Wilson, and I remember we had chicken pie for dinner with home-made beer to wash it down, To-day I have hard-tack. Have I ever described hard-tack to you? … In size they are about like a common soda cracker, and in thickness about like two of them…. But… The cracker eats easy, almost melts in the mouth, while hard-tack is harder and tougher than so much wood. I don’t know what the word “tack” means, but the “hard” I have long understood….. Very often they are mouldy, and most always wormy. We knock them together and jar out the worms, and the mould we cut or scrape off. Sometimes we soak them until soft and then fry them in pork grease, but generally we smash them up in pieces and grind away until either the teeth or the hard-tack gives up. I know why Dr. Cole examined our teeth so carefully when we passed through the medical mill at Hudson.” (August 1, 1863, Sergeant Lawrence Van Alstyne, 128th New York Infantry)

Charming. Tolkien, having served in World War I, would have been extremely familiar with hardtack and therefore would have known the misery that it was to eat day after day. I believe Tolkien’s experiences with hardtack are why Samwise was not the biggest fan of lembas, despite how good it, supposedly tasted. In fact, Samwise’s opinion on lembas, while not as unfavorable, echoes that of Sergeant Van Alystyne:

“The lembas had a virtue without which they would long ago have lain down to die. It did not satisfy desire, and at time Sam’s mind was filled with the memories of food, and the longing for simple bread and meats.” (J.R.R Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 936)

Delving further into this comparison, I believe that cram is meant to represent the British version of hardtack, while lembas represent the Australian version, otherwise known as “Anzac biscuits”. Anzac biscuits were a much more palatable version of the standard hardtack, often including golden syrup in the recipe. This mirrors how lembas were sweeter than cram and “more pleasant than cram by all accounts”.

Due to all of this, I believe that the arduousness of Sam and Frodo’s journey to Mt. Doom should be regarded in the same way as the situation of the soldiers trapped in the trenches of World War I. The extreme mental and physical strain on the soldiers fighting in World War I mirrors the experience of Sam and Frodo on their journey to Mt. Doom. One might be able to take this a step further and compare the entire story of The Lord of the Rings to the First World War since every race in Middle Earth participated. This, however, is a different discussion.

Regardless, the comparison of lembas and hardtack, as explored above, is an example of the importance of food that appears throughout Tolkien’s literature. Bilbo’s feast at the beginning of The Lord of the Rings established the characteristics of Hobbits and Bilbo himself. The extravagance of the feast and Bilbo’s shenanigans during it perfectly framed his character and set up his relationship with each branch of his family. It also gave us great insight into the nature of the Hobbits. It was much more effective to demonstrate the Hobbits’ appreciation for food by showing us Hobbits eating and drinking to such an extent that some had to be carried home in wheelbarrows than to show a hobbit building a Scooby-Doo-style sandwich and eating it. In The Hobbit as well food played an important role, with the feast thrown by Elrond in chapter 3 serving as an important stopping point in the story and could potentially be seen as a mending of relations between the Elves and the Dwarves. The dragon-tail cake in the story of Farmer Giles serves as another example of the importance of food as a literary device to Tolkien. Through all of this, it should become clear that the lembasduring the journey to Mt. Doom served an important symbolic role, emphasizing the plight of Sam and Frodo during their quest.

2 comments:

Very interesting idea. Are you indicating that you believe the Lord of the Rings is entirely an allegory for the First World War? Furthermore, how comfortable do you feel in making fairly 1:1 comparisons between 'secondary world' and 'primary world' items? These are questions that I myself have considered and am considering now. What significance do you think there is (if any) to the fact that the Hobbits survive on non-Hobbit 'hardtack'? Is this perhaps, in your view, a reflection of Tolkien's experience collaborating with other nations and eating their food? Do you think there is any resonance or importance to the fact that they specifically survive on elven bread; after all, elves are semi-immortal, so does some of this property 'rub off' on the Hobbits through elven food? Or, with the elves being the Australians and Kiwis, does their semi-immortality reflect the toughness and hardiness of the ANZAC troops in the First World War? Your blogpost has raised many questions for me which I will spend some time considering.

-LM

You need to embrace the possibility of BOTH/AND! Yes, lembas is hardtack, but it is also the communion bread, both of which are called "waybread," viaticum. There are ways in which the description of lembas as hardtack in fact enhances the understanding of the Eucharist (and vice versa): we are wayfarers in this life, according to Christian teaching, which makes us strangers and pilgrims dependent on the Eucharist for our journey. To whom does such bread seem sweet? Interestingly: those who live on nothing but waybread, as, famously, some medieval Christian mystics. So, yes, soldier's bread! Which is also the Host. RLFB

Post a Comment