In class, we’ve discussed extensively the ways in which Tolkien takes us out of the faerie and pulls us back into it. We’ve spoken about how the tale originally starts out grounded, with characters of the Hobbits that are deeply human and relatable to us. Through Book 1, we travel more and more into the faerie world, the mythical and magical world of the Elves and Dwarves. Tom Bombadil is arguably our first encounter with faerie and once we’re in Rivendell, the realisation sets in that this is a book primarily set in faerie, with powers at work that go far beyond even the imaginations of the simple Hobbits with whom we started the story. In my discussion post, I’m going to analyse how this effect of being transported from the real world to faerie and this weaving in of both elements is created through Tolkien’s use of style and the language it is written in. With this context, let us analyse in detail the Appendix F of the Lord of the Rings, which deals with Westron, the Common Speech.

On reading Appendix F, I was alarmed by the choice Tolkien made to translate proper nouns like Sam Gamgee and Wormtongue and Rivendell. It seems highly out of character for Tolkien, who prides himself on the authenticity and uniqueness of the names in his work. Stylistically, I like the choice. As Tolkien himself points out, the ordinary reader would treat both Elvish and Westron names as equally fantastical or faerie. To us, Karningul and Imladris sound equally out of place, generating the same level of fantasy. If Samwise Gamgee had instead been called Banazir, his introduction would not invoke the same feelings of simplicity, of warmth and an idyllic outlook that we associate with Sam. We saw this phenomenon with the passage about vote-counting we saw in class, which lost most of its charm when it was made clear it was about Washington DC and not a fantasy land.

However, artistically, this is an odd choice. In Letter 190, Tolkien is outraged at the translation of words like the Shire and other nomenclature to their Dutch equivalents. This is at first a pretty neurotic hang-up. If this work, and words like Shire and Wormtongue and Samwise are after all translations of their Westron equivalents, why should he care about their further translation to Dutch instead of English? Both are, in the lore, theoretically equally far-removed from Westron as one another, right? There are two possible answers to this. The first is the one I presume Prof Brown will give. This line of reasoning goes somewhat as follows: Banazir evokes the same feeling within the Legendarium that Samwise does to an average Englishman(or, possibly, to the average human in this generation). Thus the word Samwise is absolutely essential, as it ensures that we, the Readers, associate with the Shire, the same thing that Tolkien himself associated with it: an image of a backward English countryside in a pre-industrial era. To translate it would be to remove the Lord of the Rings from the English countryside that Tolkien imagined it started in. I think this explanation is,at its best, highly contrived and at its worst, it’s just wrong. Not all of us who read this book know what countryside he envisions when he writes this book, so we can’t replicate this. In fact, most of us imagine the Shire as the part of New Zealand where the film trilogy was shot, not England! This means that this choice of untranslatability is not very effective. Even if it was, if made for these reasons, I don’t think it’s a good choice. Tolkien makes his best efforts to make his sub-creation internally consistent and self-contained. To require a knowledge of the English countryside to understand Tolkien’s word choice would be a tragedy, for it would go against the meticulous work Tolkien has put in to make the Legendarium internally consistent and have its own existence out of our world. Tolkien makes every choice in his works to add more detail and believability to his work, so it’s alarming and unusual to see otherwise.

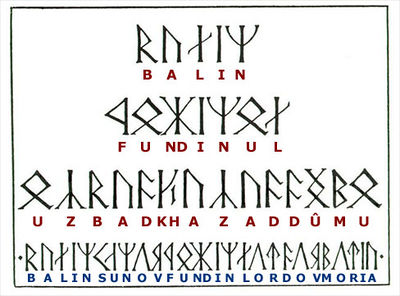

I have a better explanation: Westron is a joke! What do I mean by this? I mean that Westron was never initially conceptualised as a different language from English. Tolkien, after writing his masterpiece, thought to himself about how he could add more detail to this work. He comes up with the brilliant idea to suggest that the Lord of the Rings wasn’t originally written in English, but rather in the ‘Common Speech’, which is Westron. This is a masterful way of adding detail to the Lord of the Rings: by merely making a simple claim in two pages of the Appendix, he manages to add a whole layer of depth to the story. It makes the Lord of the Rings look even more thought out- to an almost insane level. The claims of him being capable of writing the whole novel in Elvish ( which are also not true, the Elvish vocabulary is only exhaustive thanks to fan additions) make the Lord of the Rings seem even more impressive. Here’s why this theory isn’t true. I don’t think Westron is ever mentioned by name in the Lord of the Rings, it’s always referred to as the Common Speech, which could have very well originally meant English. Secondly, there aren’t any functional differences between Westron and English, except for the existence of a deferential pronoun, as Denethor and the Court use. Except, we never see a deferential pronoun used, because the Hobbits magically don’t use it! (Could it be coincidence that the one grammatical difference between Westron and English is used by all except the tellers of our tale? I think not!). With all these hunches and vaguely thought out arguments, I started to look for better evidence for my theory. At a first glance it seems to be so: a quick search shows us that Tolkien created massive corpuses for Quenya or Sindarin or even the Black Speech, but most of the words of Westron we know are actually from Appendix F itself. The replacement and complete erasure of Westron is exhaustive: one would expect the runic inscriptions on Balin’s tomb in Moria to be reproduced as is: giving both the Khuzdul and Westronic versions as they were. Rather, we see the first part in Khuzdul, but the second part is merely English written in the dwarven runes.

This is absurd: as absurd as me taking a picture of something written in Hindi and Sanskrit, then photoshopping it so that the Sanskrit was translated and the translation was transcribed back to Devanagari, the Sanskrit script, and publishing this picture. There isn’t much work on Westron, to be honest. I think this goes to further my theory, as even if JRR Tolkien had perceived himself writing a translation, he would have added a lot more subtle hints towards this, as is his style. I stand by my belief that Westron and Appendix F is a cheeky joke to show us how much in-depth Tolkien has thought about his work and a testament to his dedication to always pushing for a consistent creation, even through post-hoc ways.

It was never Banazir Galbasi. It was always the same Samwise Gamgee we know and love.

RK

On reading Appendix F, I was alarmed by the choice Tolkien made to translate proper nouns like Sam Gamgee and Wormtongue and Rivendell. It seems highly out of character for Tolkien, who prides himself on the authenticity and uniqueness of the names in his work. Stylistically, I like the choice. As Tolkien himself points out, the ordinary reader would treat both Elvish and Westron names as equally fantastical or faerie. To us, Karningul and Imladris sound equally out of place, generating the same level of fantasy. If Samwise Gamgee had instead been called Banazir, his introduction would not invoke the same feelings of simplicity, of warmth and an idyllic outlook that we associate with Sam. We saw this phenomenon with the passage about vote-counting we saw in class, which lost most of its charm when it was made clear it was about Washington DC and not a fantasy land.

However, artistically, this is an odd choice. In Letter 190, Tolkien is outraged at the translation of words like the Shire and other nomenclature to their Dutch equivalents. This is at first a pretty neurotic hang-up. If this work, and words like Shire and Wormtongue and Samwise are after all translations of their Westron equivalents, why should he care about their further translation to Dutch instead of English? Both are, in the lore, theoretically equally far-removed from Westron as one another, right? There are two possible answers to this. The first is the one I presume Prof Brown will give. This line of reasoning goes somewhat as follows: Banazir evokes the same feeling within the Legendarium that Samwise does to an average Englishman(or, possibly, to the average human in this generation). Thus the word Samwise is absolutely essential, as it ensures that we, the Readers, associate with the Shire, the same thing that Tolkien himself associated with it: an image of a backward English countryside in a pre-industrial era. To translate it would be to remove the Lord of the Rings from the English countryside that Tolkien imagined it started in. I think this explanation is,at its best, highly contrived and at its worst, it’s just wrong. Not all of us who read this book know what countryside he envisions when he writes this book, so we can’t replicate this. In fact, most of us imagine the Shire as the part of New Zealand where the film trilogy was shot, not England! This means that this choice of untranslatability is not very effective. Even if it was, if made for these reasons, I don’t think it’s a good choice. Tolkien makes his best efforts to make his sub-creation internally consistent and self-contained. To require a knowledge of the English countryside to understand Tolkien’s word choice would be a tragedy, for it would go against the meticulous work Tolkien has put in to make the Legendarium internally consistent and have its own existence out of our world. Tolkien makes every choice in his works to add more detail and believability to his work, so it’s alarming and unusual to see otherwise.

I have a better explanation: Westron is a joke! What do I mean by this? I mean that Westron was never initially conceptualised as a different language from English. Tolkien, after writing his masterpiece, thought to himself about how he could add more detail to this work. He comes up with the brilliant idea to suggest that the Lord of the Rings wasn’t originally written in English, but rather in the ‘Common Speech’, which is Westron. This is a masterful way of adding detail to the Lord of the Rings: by merely making a simple claim in two pages of the Appendix, he manages to add a whole layer of depth to the story. It makes the Lord of the Rings look even more thought out- to an almost insane level. The claims of him being capable of writing the whole novel in Elvish ( which are also not true, the Elvish vocabulary is only exhaustive thanks to fan additions) make the Lord of the Rings seem even more impressive. Here’s why this theory isn’t true. I don’t think Westron is ever mentioned by name in the Lord of the Rings, it’s always referred to as the Common Speech, which could have very well originally meant English. Secondly, there aren’t any functional differences between Westron and English, except for the existence of a deferential pronoun, as Denethor and the Court use. Except, we never see a deferential pronoun used, because the Hobbits magically don’t use it! (Could it be coincidence that the one grammatical difference between Westron and English is used by all except the tellers of our tale? I think not!). With all these hunches and vaguely thought out arguments, I started to look for better evidence for my theory. At a first glance it seems to be so: a quick search shows us that Tolkien created massive corpuses for Quenya or Sindarin or even the Black Speech, but most of the words of Westron we know are actually from Appendix F itself. The replacement and complete erasure of Westron is exhaustive: one would expect the runic inscriptions on Balin’s tomb in Moria to be reproduced as is: giving both the Khuzdul and Westronic versions as they were. Rather, we see the first part in Khuzdul, but the second part is merely English written in the dwarven runes.

This is absurd: as absurd as me taking a picture of something written in Hindi and Sanskrit, then photoshopping it so that the Sanskrit was translated and the translation was transcribed back to Devanagari, the Sanskrit script, and publishing this picture. There isn’t much work on Westron, to be honest. I think this goes to further my theory, as even if JRR Tolkien had perceived himself writing a translation, he would have added a lot more subtle hints towards this, as is his style. I stand by my belief that Westron and Appendix F is a cheeky joke to show us how much in-depth Tolkien has thought about his work and a testament to his dedication to always pushing for a consistent creation, even through post-hoc ways.

It was never Banazir Galbasi. It was always the same Samwise Gamgee we know and love.

RK

2 comments:

I take your point: that people come to the story with different landscapes in mind, particularly from having seen the movies, but Tolkien was to a certain extent talking to himself about the feeling that the names evoked, and for him "Banazir" and "Samwise" had the same flavor. They are both invented names, neither exists in English ("Sam" as it is usually formed comes from "Samuel" not "Samwise"). You need to prove that Tolkien was imagining readers other than himself first before you can claim that he didn't mean what he says he meant. On the other hand, I agree that Tolkien still might have meant the whole thing as a (serious) joke. As we saw in our discussion of "Farmer Giles," he liked jokes very much! RLFB

Interesting theory, and plausible. If I may push back on one of your reasons: “Internally consistent” and “self-contained” are different things, and you can have one without the other. Tolkien’s world is definitely internally consistent, but I don’t think it is self-contained (i.e. complete, independent, self-sufficient). You say that “To require a knowledge of the English countryside to understand Tolkien’s word choice would be a tragedy, for it would go against the meticulous work Tolkien has put in to make the Legendarium internally consistent and have its own existence out of our world.” Are we so sure that Tolkien wanted Middle Earth to exist totally outside of our world? Would links to our world necessarily render ME inconsistent or unbelievable? Many fantasy worlds are connected to this world and remain internally consistent and believable, and we have seen a lot of evidence pointing to Tolkien’s influences and inspirations.

I think you may be right, that Westron was a de post facto detail, and Balin’s tomb is good evidence. Still, I don’t think it makes Westron less real for being added later, no more than Aragorn is less real for being added after Strider! It gives the whole more depth, and to echo Prof. Fulton Brown, we have to take Tolkien at his word—at his world as he gives it. - LB

Post a Comment